Before anyone starts arguing that semantic search doesn’t exist yet, or in the extreme, never will, let me offer a very reasonable response:

You are SO wrong! I could prove it, but that’s a topic for another post. Besides, if you really believe that, it may be your level of understanding that is questionable.

With that out of the way, we really should define semantic search in the context of this post. I think we’ll all agree that the search engines algorithms are already able to receive a search query and search its vast index and return documents that are relevant to that query. Where semantic capability enters the equation is when the algorithms are able to understand what the search query is asking for and understand what a document is really about, resulting in a tremendous improvement to the quality of search results.

We’ve all seen the cheap articles that ramble on about one topic, while dropping in a link to an entirely unrelated topic. Come on… how do Prada shoes play into an article on Brazilian tree frogs? There was a time when such tactics could actually help a shoe site rank… no more! A couple of black and white Google-mascots have made that a very hazardous and largely unproductive practice.

What does Semantic Copywriting mean?

Writing semantic copy today, with semantic search driving our methods, accomplishes three things:

[list type=”bullet3″]

- It helps the search engines understand what a document is about, within today’s semantic capabilities;

- It helps the learning algorithms build deeper knowledge of the relationships between words and entities, thus constantly improving their semantic capabilities;

- It helps make the copy more easily understood by the reader.

[/list]

The use of synonyms in web copy is a long-standing practice. Even that has become less important as the search engines learn more and more synonyms. But semantic search is about a lot more than simply associating terms like car, auto, automobile and coach with a similar meaning.

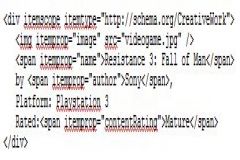

Some technical semantic mark-up, like RDFa, schema or microformats helps with the learning process, too, by providing a relatively uniform classification and cataloging of relationships and meanings. But while it does help the search engines learn about human language, it simultaneously works against the Semantic Web that Tim Berners-Lee may have had in mind.

Such mark-up languages represent an effort of humans to speak a machine’s language. True semantic search, however, focuses on teaching the machine to understand the human’s language. During the learning stages, using both may be beneficial. But at some point, we’ll be faced with deciding in which direction we want to go. We’re not there yet, but it’s probably not nearly as far away as some people think.

How do you Write Semantic Copy?

Google has been able to look at surrounding text for some time, to determine what a phrase (or even a paragraph) is about, perhaps beginning to do so in an effort to spot out-of-place anchor text. We can take advantage of that by combining a number of different techniques to make our copy more descriptive.

First of all, just because the use of synonyms is nothing new doesn’t mean it’s not still a valid tool. For instance, although keyword density isn’t a ranking factor or signal (at least, not in a positive sense), the use of synonyms for major keywords can both prevent the appearance of keyword stuffing and make the read less tedious for the user.

But semantic copywriting can go even further. By ensuring that our writing possesses continuity, we make it easier for the search engines to detect not only our topic, but also the overall statement we’re trying to make. Semantic analysis functions primarily by correlation, which given the present capabilities of the search algorithms, allows us to demonstrate relationships, to a certain extent, without the use of semantic mark-up.

The key to writing for the Semantic Web isn’t to write like a search engine “thinks”… it’s to teach the search engine how you think.

An Example, with the Possible Benefits

Consider this sample copy:

Acme’s regulating widgets are manufactured in their new state of the art, ISO9000 certified manufacturing facility in New Brunswick, Maine. The company’s 600 strong workforce has maintained zero defects since the modernized factory opened in January of 2012, and boasts of 100% customer retention for users of their flagship PR1 Series devices.

Now, looking at this, we can quickly see that the search engines would be able to detect:

[list type=”bullet3″]

- Acme opened a new plant in January, 2012;

- The plant manufactures pressure regulating widgets;

- The plant is in New Brunswick, Maine;

- The plant is ISO-9000 certified;

- The plant has 600 employees;

- The plant claims zero defects since opening;

- The plant claims 100% customer retention.

[/list]

The SE can also learn (deduce?):[list type=”bullet4″]

- a manufacturing facility, in this context, is also called a plant or a factory;

- the plant manufactures a series of regulating widgets;

- Regulating widgets are the plant’s flagship product.

While the first of the three items tagged with red bullets deals with nothing more than synonyms, it’s still important, particularly since plant can be either a verb or a noun, as well as referring to vegetation. The last two are simply more information, both for the reader and the search engine.

The real significance is that with a learning algorithm, the search engine can now have learned a great deal more. A search for regulating widgets might return the company’s site – nothing new there, obviously. More importantly, the SE would now be able to consider a number of different criteria in a search query (without any special filtering search operators) and possibly return a page that has no mention whatsoever of any terms in the query.

Consider a query for “ISO-9000 manufacturing plants” or “Maine manufacturing facilities”… the company’s About Us page might appear in the SERPs, even though the page doesn’t mention those aspects. It’s the Knowledge Graph at work!

While that example certainly doesn’t represent the scale of semantic capability that Tim Berners-Lee visualized years ago, it does take an important step in that direction. It goes beyond simply matching on-page content to query terms, and applies knowledge gained to improve the search results. Most importantly, it does so without having to access any online databases or directories of ISO-9000 certified plants or manufacturing facilities in Maine.

It’s also worth mentioning that the sample above conveys quite a bit of information to the reader, in less than 50 words, without repeating a keyword, even once. That helps keep the readability at a good level for your audience.

In Summary

When writing web copy, if you adopt a mindset of presenting additional information for the readers and the search engines, you can present higher quality copy, while helping the search engines to learn more about both your topic and human language. It’s a win-win situation, and can give more momentum to the movement toward the Semantic Web.

Synonyms are a valid method of avoiding keyword-heavy copy, but their use, combined with a writing style that considers the learning potential of the search engines’ algorithms can also greatly increase the opportunities to appear in the SERPs. Relevance can take on meanings beyond what is specifically cited in a document.

Imagine the opportunities this presents!

Great explanation of the semantic web. It’s a topic that is difficult to get a grasp on and you’ve done it well.

Thank you Robin, I appreciate your kind words